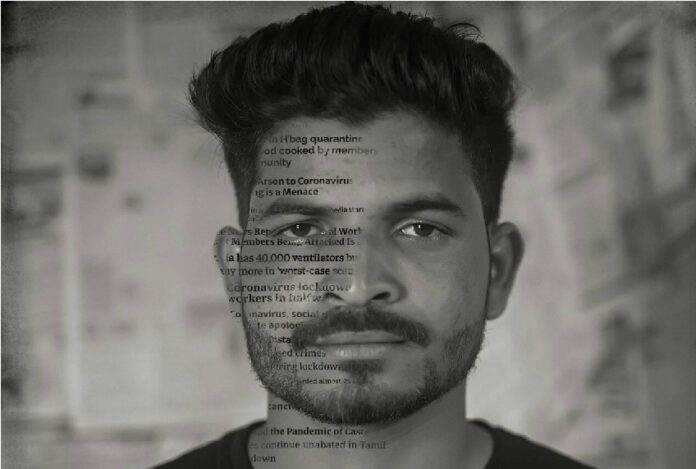

When Harish Kamble, 29, was in his late teens, he said, he had a humiliating encounter that stuck with him.

He had gone to collect a document from someone’s house in his village in southern India. The man wasn’t home so his wife asked Kamble to take a seat and wait.After the man arrived, he was furious to see Kamble, who is from a so-called lower caste, or social class, in his house. Kamble said he’s never been able to shake it off.“Till today, when I go somewhere, I think twice before going to anyone’s house. See that childhood trauma you carry with you all the time,” he said.Kamble also remembers his grandparents telling him how their land was taken away by people from the dominant caste. The injustices that his family and others from his community faced became the subject of a lot of his poetry and later, rap lyrics.In India, a new wave of Dalit artists like Kamble are using hip-hop to stand up to one of the world’s oldest forms of discrimination: caste, similar to how Black rappers in the US began channeling decades ago to call out prejudice and injustice.But this wasn’t the kind of hip-hop these artists grew up listening to. In Indian pop culture, hip-hop is associated with misogyny. The popular rappers in the country mostly sing about partying, drinking and chasing after girls.Kamble said that he used to think that’s all hip-hop was about.

“When I got to know that hip-hop is something that was started for a good cause back in the ’70s, it was all started in America, then it was very relevant for my experiences too,” he said.Since then, he said, he’s discovered a lot of American hip-hop artists — from Tupac to Kendrick Lamar.Kamble’s rap is a continuation of his family’s tradition of musical activism. His grandfather used to sing “Bhim geet,” songs about B. R. Ambedkar who fought for Dalit rights and wrote India’s constitution.In his 2019 song called “Jaati,” which means “caste” in his native Kannada language, Kamble compares caste-based thought to a tsunami.“Where is my place in this great country?” he asks.

Vipin Tatad, who grew up in a slum in the western state of Maharashtra, said that he writes about what he sees his community go through on a daily basis. His latest song includes verses about how scores of Dalits die each year while manually cleaning sewers, suffocated by the toxic gases inside.

The words go: “Those drains and gutters, why do we have to clean them?/Do we own contracts to clean them/Those gutters are filled with toxic gases/Hydrogen sulfide and poisonous methane/One fatal breath ends our life/We’re dying and you say, “let them die/Is there anything even left to talk?”

If you want to get your message across to young people, you have to rap, Tatad said.And he is getting attention.He helped create the theme song of a Netflix documentary about a serial rapist who was murdered in a courtroom in 2004 by dozens of lower-caste women, his victims. Tatad has also written a rap song for a Bollywood movie starring superstar Amitabh Bachchan.But his journey, he said, has been full of struggles. He’s been stopped in the middle of performances. He and his bandmates have to produce songs on their own, which is expensive. The income from gigs is never enough, he said.“The mainstream music industry doesn’t have space for us,” Tatad said.Likewise, most of the listeners of anti-caste rap are from the same communities as the artists. Mainstream audiences are far from accepting anti-caste rap, said Brahma Prakash, assistant professor in the school of arts and aesthetics at Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University.

He said that Indian listeners want music that soothes or heals you. But “rap is to disturb you,” he said. “I don’t think Indian consciousness in a larger way is ready for these kinds of songs.”

For now, anti-caste rappers are carving their own space — on social media. Top artists like Arivu have more than 1.5 million monthly listeners on Spotify. Some of Tatad’s songs have more than 200,000 views on YouTube. But he doesn’t think of his music as a career — it’s more of a responsibility, he said.

“If we don’t raise our voices, we will continue to be exploited,” Tatad said. “Until society treats us equally, we will carry on his musical struggle against caste.”